November 10, 2011

October 27, 2011

October 24, 2011

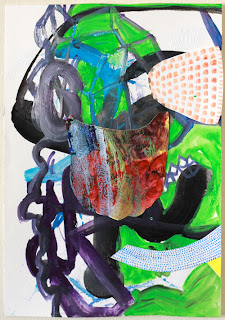

studio oct 24: Tetraptych

Finally, I have week to spend working on images! Feels great.

Plus I like tetraptychs. My drawings feel less lonely in a four image series. A family of four + polyphony.

October 19, 2011

October 17, 2011

September 22, 2011

notes sep 22

|

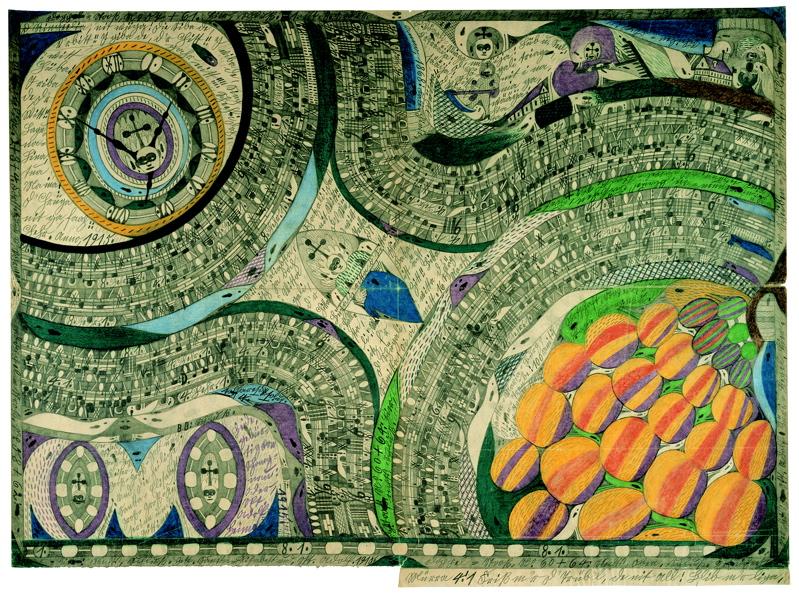

| Adolf Wolfli, General View of the Island Neveranger, 1911 |

|

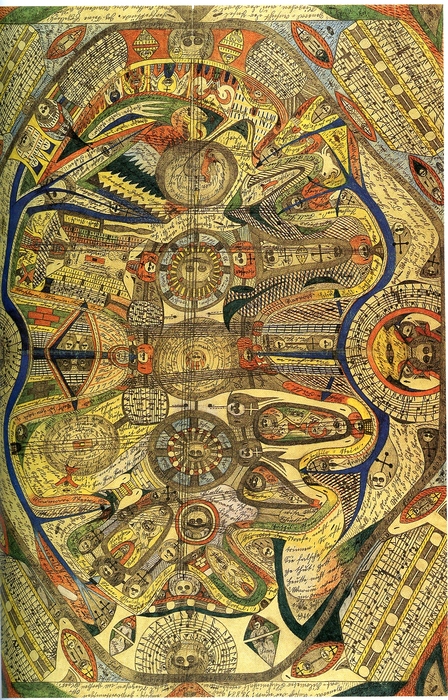

| Adolf Wolfli |

I am learning a new language and the classes and homework keep me away from working. Images and ideas are queuing up for a round about the studio, and soon there will be thought pile-up. Perhaps that is a good thing for poetry.

|

| Details from Ferdinand Cheval's Le Palais Idéal, France, 1879 - 1912 |

|

|

| Helen Martins, Interior of Owl House, South Africa, 1945-76 |

|

| Helen Martins, Garden of Owl House, South Africa, 1945-76 |

|

| Adolf Wolfli |

The concepts are muddled in my mind now: how is noise different from silence, language different from chaos, texture different from what is plain.

September 15, 2011

September 5, 2011

September 2, 2011

September 1, 2011

Books

|

| prototype for a book |

I am currently working a book project, the drawing/painting marathon, a few poems, my website, some photographs, and learning Dutch. I have been back in the studio for nearly 2 weeks now, and even with all the projects going on, I still feel the backlash of being away. Maybe there are too many projects going on, but I think that is another symptom. The studio is a very introverted space for me, and traveling disrupts some sort of physical connection or clarity pact between space and mind.

What works for me about being away however, is that I can re-evaluate the general direction of things. I am glad that I have started a book project for instance. It gives me a space to realize the polyphony of image and ideas that I carry; i.e. in a book one can combine a variety of image, word, performance etc.

The concept of 'polyphony' was first suggested to me by a professor when I was working on my graduate thesis, a four channel video projection. Polyphony (or many voices) is an quality that Mikhail Bakhtin, a philosopher and theorist from Russia, attributed to the literary works of Fyodor Dostoevsky. I read a bit of Bakhtin when I was studying cinema at JNU. Those were his works on chronotopes, hetroglossia (?), and speech genres. I will dig up those readings and go through them again...

Currently I am reading two books of interest. One is 'The Painter of Our Time' by John Berger, and the other is 'Murphy' by Samuel Beckett. Both are very different yet very fulfilling reads for me. The Painter of Our Time is a novel that reads like the diary of an artist (with comments from a friend of the artist) who disappears from Budapest in the year 1956. Berger writes,

I must go to bed. But I have not finished. I shall never finish. That is my guilt to which I confess. I have made myself doubly an emigre. I have not returned to our country. And I have chosen to spend my life on my art, instead of immediate objectives. Thus I am a spectator watching what I might have participated in. Thus I question endlessly. Thus I risk reducing the world within my own mind to my own dimensions for the sake of discovering a small truth that has remained undiscovered by others... (pg 76)

It is a very good book. And the personality of Janos Lavin, the artist, is so deeply developed and real that I often confuse the novel with an actual diary. But of course Berger's voice is part of the hetroglossia.

Beckett's Murphy is a treasure as well. There is a passage about biscuits that I like very much. Murphy, the main character, has a ritual where he eats six biscuits for lunch and Beckett describes this process.

They were the same as always, a Ginger, an Osborne, a Digestive, a Petit Beurre and one anonymous. He always ate the first-named last, because he liked it the best, and the anonymous first, because he thought it very likely the least palatable. The order in which he ate the remaining three was indifferent to him and varied irregularly from day to day. On his knees now before the five it struck him for the first time that these prepossessions reduced to a paltry six the number of ways in which he could make this meal. But this was to violate the very essence of assortment... Even if he conquered his prejudice against the anonymous, still there would be only twenty-four ways in which the biscuits could be eaten. But were he to take the final step and overcome his infatuation with the ginger, then the assortment would spring to life before him, dancing the radiant measure of its total permutability, edible in a hundred and twenty ways! (pg 62)

I've always liked cookie anecdotes.

August 31, 2011

August 29, 2011

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)